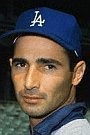

Sandy Koufax was one of the most dominant pitchers in the history of baseball, and at the age of 36 was the youngest to ever be enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

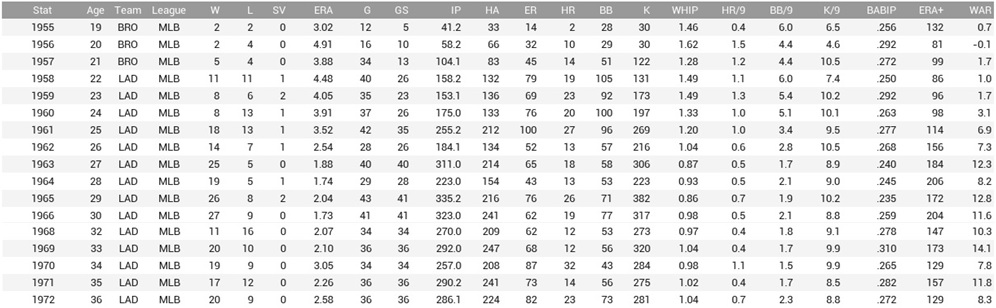

(Source: Baseball-Reference.com)

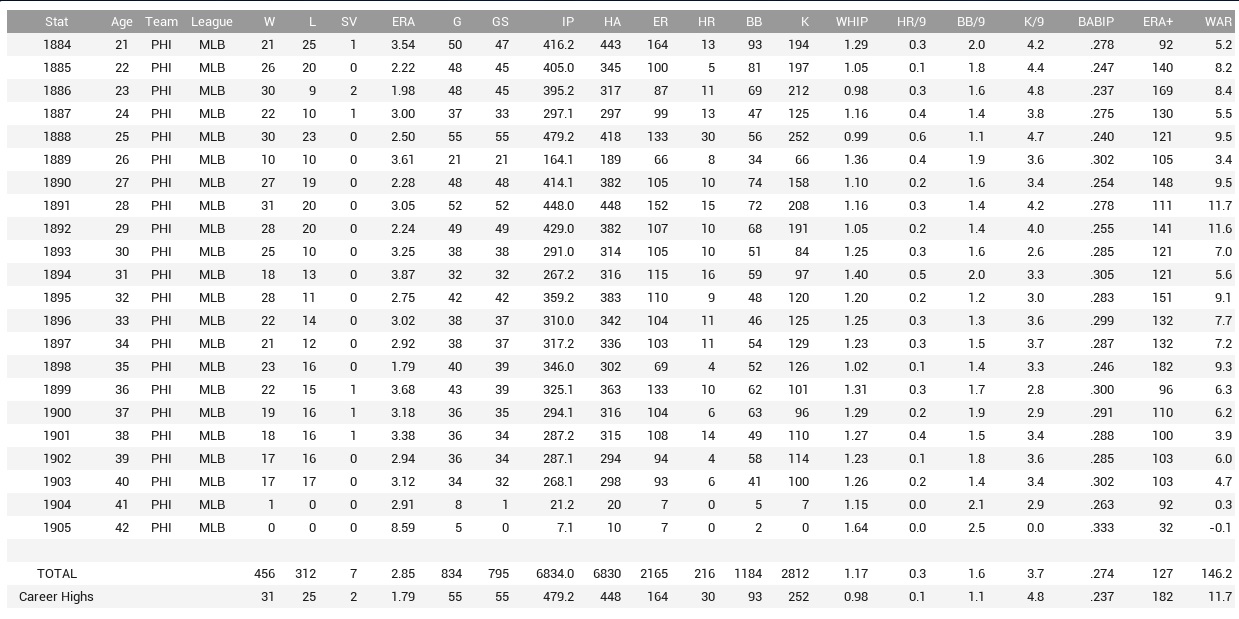

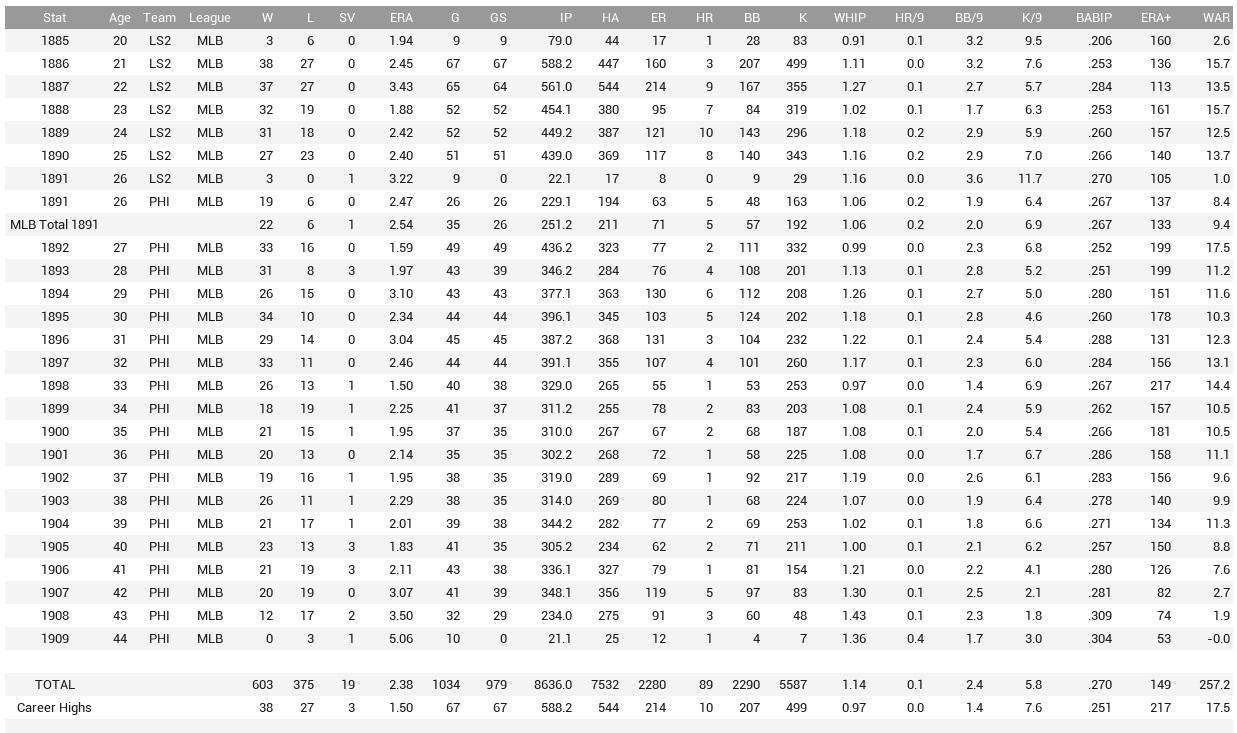

(Source: Baseball-Reference.com)

The reason for his enshrinement at such a young age was due to his early retirement due to an arthritic condition in his elbow. He pitched the entire ’65 and ’66 seasons in extreme pain but still dominated, pitching over 320 innings in both seasons going a combined 53-17 with 699 strikeouts – and winning the Cy Young both years.

Koufax retired shortly after the 1966 World Series at the age of 30.

Dr. Frank Jobe once said that Koufax had basically the same injury as Tommy John, and that if he had developed the pioneering surgery ten years earlier (Dr. Jobe was already 41 by the time Koufax retired) the surgery would likely have been named after Koufax instead.

We always find it interesting to play out these “what if” scenarios that abound in baseball, so naturally we wanted to see what might have happened if Sandy Koufax had been able to extend his career.

As always, we used OOTP16, starting a historical league on January 1, 1967. In this world, Koufax became the pioneer for the ligament replacement surgery. Having undergone the surgery immediately after the ’66 World Series meant Koufax would likely be ready to play again by the beginning of the ’68 season.

Without Koufax, the ’67 Dodgers slipped back as their offense struggled, finishing the season 82-80, 17 games back of the Cardinals. But it was their hitting instead of Koufax’s absence that was the major reason, as the Dodgers hit a collective NL worst .236 with a lowly .627 OPS.

Koufax was ready to take his rightful place as the ace of the staff at the beginning of the ’68 season. His first start on Opening Day was against the Phillies. Whether rust or nerves got the best of him, he gave up 3 hits, a walk, and 3 runs in the opening frame. He settled down after that, giving up 7 hits over the final 8 frames for a complete game, but the damage was done and the Dodgers lost 3-2.

A no-decision and a tough luck 1-0 loss dropped him to 0-2 before Koufax really caught his groove, throwing 23 straight scoreless innings. He would improve his record to 4-3 before arm troubles would once again strike. He missed two starts with inflammation and struggled once he came back, uncharacteristically dropping 5 straight decisions, including 2 in which he gave up 5 earned runs. But he bounced back with a complete game shutout of Cincinnati to go into the All-Star break. Despite a 5-8 record, his 2.17 ERA, 0.98 WHIP, and 5.2 WAR was good enough for a spot on the All-Star team.

Meanwhile the Dodgers were rebounding from their lackluster ’68 season and were leading the NL at the break – but 5 other teams were within 4.5 games.

Right after the break Don Drysdale wrecked his elbow and would miss the remainder of the season. Without Drysdale and with a completely anemic lineup, the Dodgers couldn’t hold it together in the second half. They plummeted down to 6th place, 10 games behind the NL champion Phillies.

Koufax finished his comeback season with everything except his W-L record resembling his prior dominant years. He ended 11-16, but with a 2.07 ERA, 273 Ks in 270 IP, and a 10.2 WAR. He led the league in strikeouts, WAR, complete games (18), and shutouts (7). Voters didn’t hold his record against him, as he won his 4th Cy Young award.

In ’69 with the new NL alignment, the Dodgers still couldn’t quite get it altogether. Shortcomings at the plate were not addressed during the offseason and Drysdale would miss the entire season as well. Though they finished with a winning record (87-75) the Dodgers finished only 4th in the new NL West, 15 games behind the Astros.

Koufax was still in prime form, however. He finished the season especially strong, going 8-1 over his final 10 starts, 6 of which were complete games. Even with the higher pitching mounds introduced in ’69, at no point during the entire season was his ERA over 2.66. Once again he led the league in strikeouts (320) and WAR (14.0), going 20-10 overall with a 2.10 ERA. He would win both the Cy Young and MVP Award in that season.

The 1970’s arrived and the now 34-year old Koufax wasn’t losing a single step. Again he led the Dodgers’ pitching staff and dominated opposing hitters. A mid-August swoon where he gave up 26 ER over 5 starts was the only blemish, though that period was attributed to some lingering arm issues which caused him to miss 2 starts. Once he returned he went back to his old form, winning his last four decisions.

With Drysdale back, the two of them anchored the pitching staff. The previously anemic Dodgers lineup was bolstered by the production of Al Herrera, who hit 24 HR, a young Steve Garvey, and the acquisition of Earl Williams as the number one catcher, who smashed 40 HR. With all the pieces in place, the Dodgers won the NL West, going 92-69.

Koufax and the Dodgers would face the Phillies for the NL Championship, with Koufax pitching game 1 against Rick Wise. Wise outperformed Koufax pitching 7 shutout innings of 5-hit ball in a 3-0 win. The teams would split the next two before Wise and Koufax would square off again with the Dodgers facing elimination. This time Koufax came out on top 3-2, thanks to a two-run HR from Williams. Drysdale would finish them off in the 5th game and the Dodgers went on to face the Tigers in the World Series.

Koufax was excellent in his first World Series start since 1966, pitching a complete game 4-hitter with a sac fly as the only run scored. Unfortunately for him, the Tigers had acquired Jerry Reuss who pitched a shutout and the Dodgers lost 1-0. Once again the teams would split the next two games and Koufax would face Reuss in Game Four. Koufax pitched another complete game winning 5-1. The teams would again split the next two games setting up another Koufax/Reuss matchup for the 7th and decisive game.

Koufax cruised through the first 3 innings but in the 4th was forced to exit the game as his arm acted up yet again. The bullpen pitched admirably but a solo shot by Jim Spencer in the 5th was the only run of the game and the Tigers blanked the Dodgers to win the World Series. For Koufax it was a heart wrenching end to an otherwise brilliant season.

1971 was another down year for the Dodgers – their worst since 1958 winning only 75 games. There was one bright spot, which occurred on July 21st. Koufax took the mound and pitched a complete game 7-hitter against the Reds to win his 200th career game. He finished that season 17-12 with a 2.26 ERA and 11.9 WAR, good enough for his 6th Cy Young.

He would win 20 games again in 1972 to go along with a 2.58 ERA and an 8.3 WAR. On October 3rd he took the mound against the Atlanta Braves who got to him early and often. While he stuck it out to go 7 innings, he tied his career high by giving up 9 earned runs. That outing was topped off by a 2-run HR by Hal McRae. It would be the last pitch Koufax would throw, as he retired at the end of the season at age 36.

Coming back from Tommy John surgery extended Koufax’s career 5 full seasons and allowed him to reach the 200-win milestone along with winning 3 more Cy Youngs and one more MVP. He finished 252-143 with a 2.62 ERA and a career 116.8 WAR. While Koufax certainly wasn’t the only factor, he contributed to giving the Dodgers one extra NL championship than they did in real life, but his arm let him down in the most important game.

So would Koufax coming back have positively or negatively affected his legacy? He still didn’t rack up 300 wins, but his 6 Cy Young Awards would today be second only to Roger Clemens (7) – a number made more impressive by the fact that before his injury it was a combined AL/NL award. Add to that the likelihood that Tommy John surgery would have been called Sandy Koufax surgery makes us wish Dr. Frank Jobe had developed his groundbreaking surgery earlier.

Follow us on Twitter @BullpenByComm